By Louis DiPietro

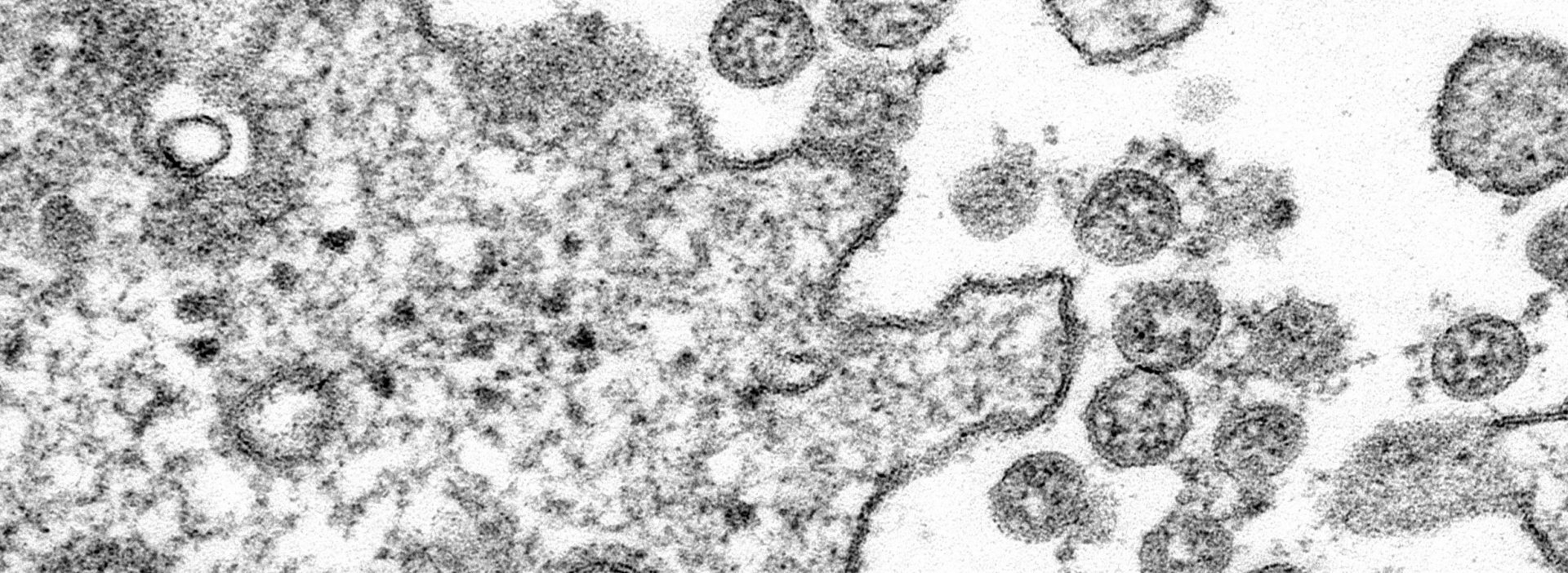

A Cornell-led COVID-19 patient registry, organized by Weill Cornell Medicine physicians and scientists in response to surging cases earlier this year in New York City, continues to be a source of medical insight into the workings of the new coronavirus and treatment of infected patients.

Illustrating the power of interdisciplinary cross-campus collaboration, a team of Weill Cornell Medicine physicians and PhD scientists based in New York City, along with student statisticians collaborating remotely from Ithaca, NY, and elsewhere, have built a secure database with medical data on more than 4,000 patients who had clinical symptoms of COVID-19 and were seen at one of three NewYork-Presbyterian Hospital campuses. From this registry, medical professionals are learning more about how to treat patients with COVID, which has thus far claimed 1.5 million lives around the world, according to latest statistics.

“COVID-19 accelerated everything,” Rajan said. “The fact we were thrown into this situation has spurred innovation and collaboration. There was no other choice.”

With this registry, Weill Cornell Medicine researchers are posing specific questions about COVID-19 and the SARS-CoV-2 virus that causes it — for instance, are cancer patients more susceptible to worse outcomes if infected? Is there a correlation between NYC infections and housing density? — while collaborating data-science students are using statistical modeling to crunch the patient data for answers. Through this remote collaboration, this Cornell team of physicians, PhD scientists, and statisticians — from seasoned doctors and faculty members to data-science graduate and undergraduate students — are relaying to the medical community fresh findings about COVID-19, including better methods for treatment.

“We understand that careful observational science has the potential to help front line physicians make informed management decisions,” said Dr. Monika Safford, Chief of Weill Cornell Medicine’s Division of General Internal Medicine and the John J. Kuiper Professor of Medicine, and one of the co-leaders in developing the registry. “While the initial impetus for forming the registry was to inform clinical care in a data void, the full potential of the registry was realized with studies that were less urgent in nature but nevertheless made important contributions.”

From this registry alone, the institution’s researchers have published 20 peer-reviewed papers inside of six months in major medical journals, and there are several more ongoing, according to Dr. Laura Pinheiro, an assistant professor of health services research in medicine in Weill Cornell Medicine’s Division of General Internal Medicine and a member of the registry’s overseeing executive committee.

Among the published findings Cornell researchers have shared:

- The first from-the-front-lines report of clinical characteristics of COVID-19 patients in the US, published in mid-April.

- Signs of damage to the right side of the heart may indicate a greater risk of death due to COVID-19.

- Patients with cancer who tested positive for COVID-19 had similar outcomes compared with matched patients without cancer.

- The greater the number of virus particles, the greater the risk of mortality.

Dr. Pinheiro, along with Mangala Rajan, Research Associate in Medicine in Weill Cornell Medicine’s Division of General Internal Medicine, work in tandem to manage the registry and review proposals for research. Dr. Pinheiro works on the analytics side, helping to staff different research projects related to the registry’s patient data, while Rajan oversees the operational requests for leadership and manages the data requests from researchers using the data.

“COVID-19 accelerated everything,” Rajan said. “The fact we were thrown into this situation has spurred innovation and collaboration. There was no other choice.”

Under the leadership of Drs. Safford and Parag Goyal, also of Weill Cornell Medicine, the registry was conceived in March as COVID-19 cases began to climb in New York City and as area doctors rushed to treat people infected by a virus with many unknowns. To handle the influx of patients with COVID-19, Weill Cornell Medicine and NewYork-Presbyterian Hospital converted several operating and recovery rooms into new intensive care units, and physicians and nurses left their usual assignments to help with the COVID-19 response.

Detailed patient data would be the key to shedding some light on how this novel coronavirus disease worked and what strategies were best for treatment. Recognizing this, Dr. Safford pulled together a team to create a registry of COVID-19 patients just a week after the first patient was admitted. Weill Cornell Medicine medical students, eager to actively contribute to COVID-based needs and efforts, were invited to review the medical charts of patients who tested positive for COVID-19 at NewYork-Presbyterian/Weill Cornell Medical Center, NewYork-Presbyterian Queens, and NewYork-Presbyterian Lower Manhattan Hospital. The medical students extracted and recorded data from the charts — symptoms, demographics, and more — into a secure, online registry that eventually grew to 4,100 patients, Pinheiro said.

Marty Wells' “corps d’elite” of statistics students is Ben Baer and Sara Venkatraman, both doctoral students; Matt Armstrong, a master’s student in Applied Statistics; Sivateja Tangirala, an SDS undergraduate, and Cam Hogan, a senior at Brigham Young University.

With the registry came the opportunity to glean insights into COVID-19 from a large patient data set, and Dr. Safford and the faculty team within the Division of General Internal Medicine invited the entire institution’s clinicians and researchers to propose studies that met scientific integrity standards. They were overrun by requests from Weill Cornell Medicine researchers in various departments and specialties who were eager to test their theories about COVID-19 against clean patient data, according to Rajan.

By way of the registry, researchers now had the raw data. What they needed now were statisticians to help analyze the data for insights, and to do so quickly. Dr. Safford called on an upstate colleague with whom she had previously collaborated: Marty Wells, chair and Charles A. Alexander Professor of Statistics and Data Science at Cornell University.

“When COVID-19 hit New York City hard, the scientific research community mobilized, and consequently there was excess demand for statistical analysis,” said Wells, who also serves as an advisor to Statistics and Data Science students collaborating on the registry. “The Weill Cornell Medicine researchers had the important data thanks to the medical students, but those colleagues needed careful statistical analysis to understand what findings the data contained. That’s where our students came in.”

Based at Cornell’s Ithaca campus, Wells organized a “corps d’elite” of undergraduate, graduate, and doctoral statistics students who could remotely access the registry and help crunch the data for the approved projects. That team includes: Ben Baer and Sara Venkatraman, both doctoral students; Matt Armstrong, a master’s student in Applied Statistics; Sivateja Tangirala, an undergraduate who founded Cornell’s Biomedical Informatics Club, and Cam Hogan, a senior at Brigham Young University.

The young team went through checks with the institutional review board and completed necessary certification classes — after all, the students were viewing sensitive patient information. After a few short weeks, they went to work on the registry, applying their unique skill sets to an especially dire global health crisis.

Baer and Venkatraman, the doctoral students in Statistics and Data Science, have been involved with the registry since May, lending their statistical-modeling expertise to four COVID research projects.

Baer has worked closely with NYC-based clinicians to find the clinical factors that predict the likelihood of a discharged COVID patient returning to the hospital. Another project has Baer crunching patient data to determine mortality rates for COVID patients treated with two different approaches to mechanical ventilation. The standard approach recommended by pulmonary critical care experts was to intubate patients and ventilate them mechanically as soon as they began to deteriorate. However, early in the outbreak, hospitals began to run out of ventilators, requiring a different approach that delayed intubation. Fears were real that this delay would lead to higher mortality. A careful analysis would be needed to determine whether these fears were founded.

“Since COVID has become an inescapable part of life, it was exciting to get involved in some way,” Baer said.

For Venkatraman, her work centered on demographic and socio-economic factors that led to high infection rates. Mining data from the patient registry, New York City Department of Health & Mental Hygiene, and the U.S. Census Bureau, Venkatraman found that the rate of infection in overcrowded neighborhoods of New York City — households with more than one person per room — was significantly higher than in less dense neighborhoods.

This finding may seem obvious — it’s assumed that densely populated neighborhoods with people living in close quarters would have higher rates of infection — but testing theories like this is essential, Venkatraman said.

“Statistical analysis allows us to quantify the effects of factors like housing density and provide a margin of error,” she said. “In general, the data helps us identify which neighborhoods are most vulnerable, due to their housing conditions or otherwise, which I think can be helpful for medical resource allocation and the upcoming vaccination campaign.”

Taking her analysis further, Venkatraman and her Weill Cornell Medicine collaborators learned that infection rates in both low- and high-density neighborhoods did slow after city schools were closed in mid-March and once social distancing measures were put into practice. Even with these changes, however, infection rates remained much higher in crowded neighborhoods, the Cornell researchers found.

“One takeaway from our analysis is that even people who live alone in a crowded neighborhood are at higher risk of infection than those who live alone in less dense areas," she said.

Findings from these specific research projects are to be published once the papers have been finalized.

Both students said they each put in roughly 10 hours per week on the COVID research projects, this on top of their regular course work. They commended the collaborative experience thus far, highlighting the real-world application of their work.

"As doctoral students, our primary research is often focused on developing new statistical theory and methods,” Venkatraman said. "It's been nice to see an example of how other researchers use statistics and data science in real-life applications."

“I’m not totally sure what I want to do with my career,” Baer added, “but being around the clinical and medicine fields, I’m now leaning toward biostatistics. I’ve enjoyed this enough to think about this type of work for a career.”

Teaming up with advanced statistics students had distinct advantages for the Weill Cornell Medicine researchers. For starters, they already knew modeling software, said Rajan, the Weill Cornell Medicine co-lead.

“It took less time to get them up and running. To work under a time crunch and in reality situations, which is different from a classroom, is very useful for them,” Rajan said. “Overall, they’ve been a productive bunch.”

Rajan also recognized Weill Cornell Medicine’s Architecture for Research Computing in Health (ARCH) group, whose technological know-how allowed participating students to safely access the registry and other electronic medical record data as needed.

To Wells, these kinds of partnerships within the Cornell network illustrate the university’s collective intellectual might and allow for ground-breaking collaborations. “This has been a great experience that appeared out of thin air and reveals the importance of ongoing cross-campus relationships,” he said.

It’s a collaborative spirit that all involved — Safford, Wells, Pinheiro, Rajan, and the Statistics and Data Science students — hope continues. In fact, Wells and Safford have pitched the idea of resuming this collaboration of medical and statistical minds through a new internship program.

“Having this cross-campus collaboration is vital because, when you need something, you have those relationships and expertise to draw on,” Wells said. “It would be difficult to have such collaboration materialize without them.”

Louis DiPietro is the communications coordinator in the departments of information science and statistics and data science.